Advanced Lane Line Detection

Github repo found here

Advanced Lane Line Detection

Here we will present some classical computer vision techniques on how to identify nearby vehicles and lane lines.

The goals / steps of this project are the following:

- Compute the camera calibration matrix and distortion coefficients given a set of chessboard images.

- Apply a distortion correction to raw images.

- Use color transforms, gradients, etc., to create a thresholded binary image.

- Apply a perspective transform to rectify binary image (“birds-eye view”).

- Detect lane pixels and fit to find the lane boundary.

- Determine the curvature of the lane and vehicle position with respect to center.

- Warp the detected lane boundaries back onto the original image.

- Output visual display of the lane boundaries and numerical estimation of lane curvature and vehicle position.

Important files:

- LaneFinder.py

- LaneLinderFinder.py

- lanelines.py

- settings.py

- helpers.py

- Perspective transform.ipynb

- Camera_calibration.ipynb

We will break Lane Detection down into three stages:

Stage 1: Camera Distortion

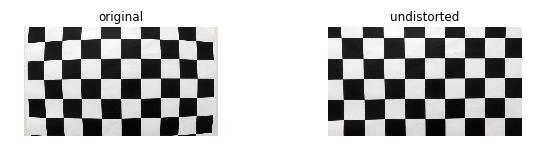

- Our video stream was captured using a monocular camera. As such, we must correct the distortion that may occur. To do this, I used openCV’s

drawChessboardCoenrsandfindChessboardCornersfunctions. I then created two lists,object_pointsandimage_points. Object points describe’s where each pixel in the image exists in a real world representation (X, Y, Z). Where image_points describe where each of those pixels are in the 2D .png image. We then compute the transformation matrixmtxand the distortion coefficient matrixdist, save them to a pickle file, because later on in stage 3 we will recall and use them incv2.undistort(). - Code for this stage can be seen in Camera Calibration.ipynb

- You can see the original and undistorted images below

Stage 2: Perspective Transformation (inside Perspective Transform.ipynb):

- Our goal in this stage is to find source and destination points that we can use to warp our perspective to obtain an aerial view of the road.

- This will allow us to calculate the distance in meters per pixel between the lane lines

- It is also easier to work with the warped image inside the laneLine’s objects, because we are dealing with straight vertical lines instead of angles lines.

-

(it’s easier to see if our predicted lines are well drawn compared to the given lanes).

- Steps in this stage

- Read in the image

- Undistort the image (using the transformation matrix and distortion coefficients from

Camera Calibration.ipynb - Convert the image to HLS

- Apply canny edge detection on the Lightness layer of the HLS image. (This gives us a better representation of the lane lines).

- Apply the Hough Transform to obtain coordinates for lines that are considered to be straight

Finding the vanishing point:

The vanishing point in an image is the point where it looks like the picture can go on forever. If you recall photos of a sunset of a horizon where they appear to extend forever, that’s the point we are looking for.

- a vanishing point is a point in the image plane where the projections of a set of parallel lines in space intersect.

- After we applied the Hough Transform we get coordinate sets inside a list

- The vanishing point is the the intersection of all the lines built from the coordinates inside that list

- It is the point with minimal squared distance from the lines in the hough list

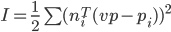

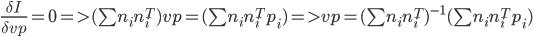

- The total squared distance

-

(1)

(1) - where: I is the cost function, ni is the line normal to the hough lines and pi are the points on the hough lines

- Then we minimize I w.r.t vp.

(2)

(2)

Finding source points:

To find the source points using the vanishing point

vp, we had to be clever.- So we have the vanishing point, which we can consider to be in the middle of our image. We want to locate a trapezoid that surrounds our lane lines.

- We first declare two points

p1andp2which are evenly offset from the vanishing point, and are closer to our vehicle. - Next, we want to find an additional two points

p3andp4that exist on the line that connects p1 and vp, and p2 and vp. - After that we will have the four points for our trapezoid (p1, p2, p3, p4), p1 and p4 live on the same line as do p2 and p3.

- We apply the equation (y2 - y1) = m (x2 - x1) and y = mx + b, and solve for x. (That is why we are using the inverse slope). This can be seen in

find_pt_inline - p1, p2, p3, and p4 form a trapezoid that will be our perspective transform region. our source points are [p1, p2, p3, p4].

- The source points define the section of the image we will use for our warping transformation

- The destination points are the where the source points will ultimately end up after we apply our warp. (pixels will be mapped from source points to destination points)

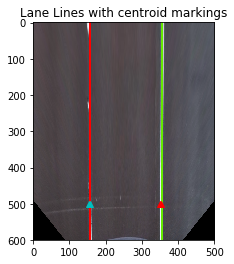

- Here you can see the vanishing point (blue triangle)

- Here you can see the Trapezoid mask we will be using for our perspective transform. The source points are marked with the + and ^ dots.

Finding the distance

- A lot of the methods applied here were suggested by ajsmilutin in this repository.

- We use moments in order to find the distance between two lane lines in our warped images.

- Lane lines are ~12 feet apart in the real world. We can use this info to find out how many pixels in our image equals 1 meter.

- We find the area between the lane lines using the zeroth moment, then we divide the first moment by the zeroth moment to get a centroid, (the center point) for both the right and left lane lines in the x-dimension.

- Now we find the minimum distance between the two centroids and define that to be our lane width. Then convert the lane width from feet to meters and now we have our pixels per meter in x. In our warped image there is no depth, it is planar. Therefore the Z in our homography matrix is 0. With that information, now all we have to do is determine the y-component from the x-component. We do this by scaling the x-dimension slot in the homography matrix by the y-dimension slot. Then we multiply that scaled value by our x_pixels_per_meter to obtain the y_pixels_per_meter.

- x_pixel_per_meter: 53.511326971489076

- y_pixel_per_meter: 37.0398121547

- You can see the centroids as the marked points in this image

- Then we save everything to a pickle file and move on to our lane line identification stage.

- Code for this stage can be seen inside Perspective_Transform.ipynb

Stage 3: Lane Line Identification (inside LaneFinder.py and LaneLineFinder.py)

Step 1: Lane detection (LaneFinder.py)

Preprocessing:

- First we undistort the image

- Then we warp the image into an aerial view

Filtering: (in LaneFinder.py)

- We first create two copies of our warped image, an

hlsand alabcolorspace copy. - apply a median blur to both copies

Detect yellow lane:

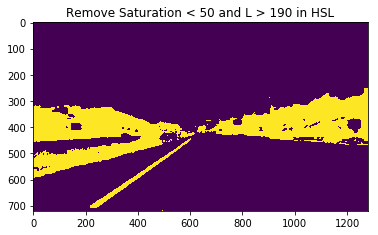

- Restrict hue values > 30 because lines should typically be a similar color angle

- Restrict saturation values < 50 because it is just noise at this point

- Cutoff lightness values > 190

- AND the hls filter with the b layer in

lab, for which values > 127.5 correspond to yellow - Everything up to this point that we have detected is the nature (trees to the left and right of the lane)

- Create a mask that is everything EXCEPT this nature piece (NOT)

- AND the mask with lightness values < 245

- Perform morphological operations: Opening followed by Dilation. Which is considerd

Tophat - Kernel sizes were selected manually through trial and error. A larger kernel rules out more noise, and a smaller kernel is designed to pick up small disturbances.

- Tophat the

lab,hls, and theyellowfilter. Tophat reduces noise from tiny pixels. Tophat = opening + dilation. Read about it here - See the filters here:

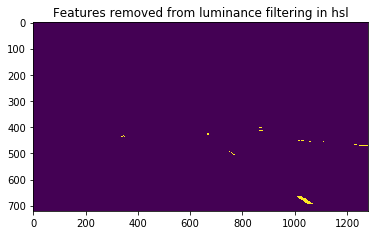

- This is what the

hlsluminance filter picked up: -

- Here is the

hlssaturation filter -

- Here is the region of interest filter (after we NOT the nature part)

-

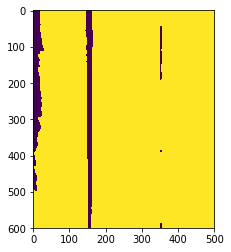

- Then we perform adaptive thresholding (LaneFinder.py)

- Then we combine this mask with the roi_mask to create a difference mask (shown below)

-

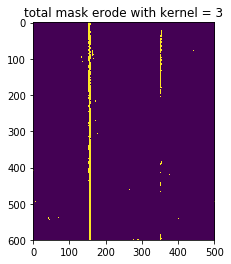

- Then we perform erosion on the difference mask to obtain the total mask.

- I tried using 5x5 kernels at first for this erosion step. Ellipses were the best kernel shape because they will erode isolated pixels, but when the kernel size was (5, 5) it was too large and it started to erode the pixels that correspond to dashes inside the lane lines. So (3, 3) was the best option, even though occasionally it may remove pixels in between the lane lines.

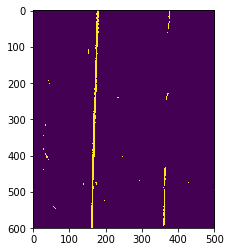

- Now we pass this binary mask into our LaneLineFinder instance.

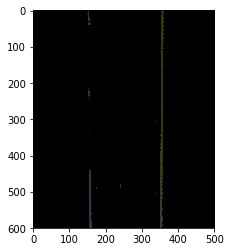

Step 2: Line detection (LaneLineFinder.py)

- Input:

-

- The LaneLineFinder finds one lane line, either left or right given a warped image (aerial view)

pt1: LaneLineFinder get_initial_coefficients

- Take the bottom vertical half of the image and compute the vertical sum of the pixel values (histogram)

- Find the max index, and use that as a starting point

- Then search for small window boxes from the bottom up to find the max pixel density (that is where the lane lines are)

- Save the good centroids to a list

- Calculate the coefficients for the equation f(x) = ay^2 + by + c. You can see this line 188 as the result of np.polyfit

pt2: For the next frame, use get_next_coefficients

- Since we know where the lane lines were from the first frame, we don’t have to start our search from scratch.

- Scan around the previous coefficients for the next lane line marking within a reasonable margin (line 77)

- We look within a margin for the next point, instead of scanning the entire image from scratch again

- If there is a large deviation from the average, then our line is not good, and we set our found property to false, then in our LaneFinder we will use the previous good line instead of this line

- You can see this feature in the video stream. When the lane line starts to drive off and deviate from the previous line it resets back to the previous good line

- Now we have the coefficients

pt3: Use get_line_pts

- Here we pass in the coefficients and receive our X and Y values to plot.

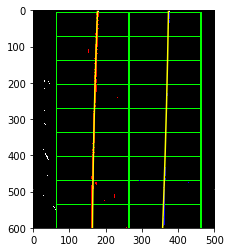

pt4: Use draw_lines

- Here we take in the x and y coordinates as

fitxandplot_yrespectively - Then we calculate our lane points and fill a window with cv2.fillPoly. This gives us extra padding on the left and right of the line so it looks thick

- Then we pass our lane points into

draw_pwwhich draws each segment inside a for loop - Then we return the drawn lines to LaneFinder

- If the line wasn’t detected we simply use the previous lane line.

pt5: Calculate curvature

- inside get_curvature line we calculate the curvature following this procedure

- We use the x_pixels_per meter and y_pixels_per_meter that we found in our perspective transform notebook (stage 2)

last part: Receive lines in LaneFinder

- Then we receive the lines for the left and right lane line as LaneFinder.left_line and LaneFinder.right_line respectively.

- Then we use cv2.add_weighted with the warped image and the combination of both the lane lines.

- Then we unwarp the image and return it

- I calculated the center place using the last fit coordinates of the left and right lines

- I used the left fit coordinate and the right fit coordinates to determine the accurate indices to draw the middle lane.

Reflection

- I attempted to structure my basic outline similar to how ajsmilutin did in this repository. However my implementation details and methods are far different. I experimented with many different kernels, and it turns out, the ones he used in his process are the best. I tried to prove him wrong and use (29, 29)’s for the first erosion, but it ended up not working properly.

- In fact. I used a lot of what he did, and it took me a LONG time to wrap my head around how it works. The OOP structure he uses in his implementation was new to me, because I don’t have that much experience with OOP programming in python, so I learned a lot by trying to reproduce what he did, except I did it in a very different way. I used an adaptive thresholding technique instead of doing sobelx, sobely, and magnitude gradients because it proves to be far better in performance on the challenge video. Even though I couldn’t get the challenge video to work well for my implementation. Credit where credit is due, I learned a TON about filtering from ajsmulitin.

- I should have created a reset option, so that if the detected line deviates too far from the average we will do a complete reset and then look for the next line as if it was the first line. This would help solve the challenge video.

- I still need to create an averaging function so that the drawn lines are drawn from the coefficients of the previous 5 frames for smoothing.

- I also received the idea for using the histogram from Udacity’s starter code.

- Originally I tried using a convolutional window, but it proved to not work as well. I was using a rectangular window for a very long time, and it was receiving outputs that did not correspond to the index of my max argument. Later on I discovered that I should be using a gaussian filter, so that the peak will be clear.

- I would not have been able to figure out how to use moments to find centroids with ajsmulitins code. It was hard for me to disect his code and see exactly what it was doing. Not an easy task.

- Special thanks to Kyle Stewart-Frantz who helped me think about how to find the deviations

- Originally I was working with jupyter notebooks, and then I got pycharm and my life changed when I figured out how to use the debugger. Completely necessary!!

- I used a pandas dataframe to test individual image sequences without having to process the entire video.I converted the video into a csv and img folder. The code for this can be seen in VideoAcquisition.ipynb

Twitter: @jonathancmitch

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/jonathancmitchell

Github: github.com/jonathancmitchell

Medium: https://medium.com/@jmitchell1991

Tools used

Written on April 1, 2018